Year three clinical trial results on Abbott Vascular’s next-generation dissolvable stent were discouraging across the board, but the device still has promise—as investigators participating in ongoing trials in the U.S. should help demonstrate. These researchers are more familiar with the unique requirements regarding vessel preparation/sizing prior to stent deployment.

The uniformly poor performance of Abbott Vascular’s Absorb GT 1 Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold device was the major headline out of the 2016 Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics meeting Oct. 29 – Nov. 2 in Washington D.C. The first two years of data out of Europe on the next-generation stent looked promising based on the non-inferiority design of those initial studies. But the ABSORB II trial, based on three years of data, found every one of the stent’s unique theoretical benefits to be untrue; moreover, angiographic and clinical outcomes were worse than in patients who instead had the company’s everolimus-eluting, permanent polymer Xience stent.

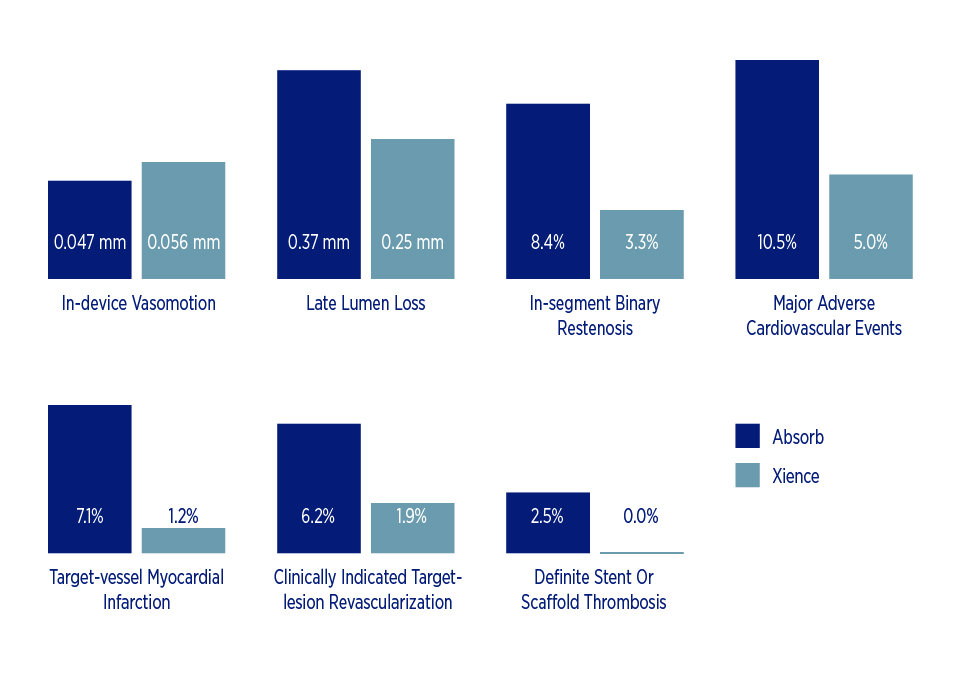

One of the big hopes with the Absorb stent was tied to the idea that eliminating a physical metallic scaffold from inside a blood vessel would allow the vessel to regain its original vasomotion so it could constrict and dilate normally, enabling a healthy endothelium to produce nitric oxide. Similarly, if a future coronary artery bypass graft were necessary, the distal anastomosis location would not be impeded by a metal scaffold, potentially improve the odds of surgical success. But the latest study findings among patients with coronary artery disease show Absorb comparing poorly to Xience in terms of:

- Notably less in-device vasomotion – 0.047 mm vs. 0.056 mm, p=0.49

- Significantly greater late lumen loss – 0.37 vs. 0.25 mm, p = 0.0003

- Higher rate of in-segment binary restenosis – 8.4 percent vs. 3.3 percent, p=0.04

- Higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events – 10.5 percent vs. 5.0 percent, p = 0.04

- Higher rate of target-vessel myocardial infarction – 7.1 percent vs. 1.2 percent, p=0.006

- Higher rate of clinically indicated target-lesion revascularization – 6.2 percent vs. 1.9 percent, p=0.036

- Higher rate of definite stent or scaffold thrombosis – 2.5 percent vs. 0 percent, p=0.06

The results are particularly worrisome for the hundreds of patients who participated in the ABSORB II trial, which was essentially a general release of the product into the European market using current approaches to stenting that may not involve considerations for vessel preparation, imaging to measure exact sizing (even a 1 mm difference in this particular stent spells the difference between failure and success), and high pressure deployment inflations precisely matched to the reference vessel. Since the Absorb stent is comprised of plastic rather than metal, successful deployment requires that it be sized exactly right for the target vessel. Picking a stent based on an angiogram or eyeball calculation, and then “sizing up” as necessary with a larger diameter angioplasty balloon (as operators traditionally have done) may potentially break the horizontal struts, reduce vessel coverage and provide an opportunity for either acute clots to develop or eventual restenosis due to uneven distribution of the drug.

The fact that the stent hadn’t fully dissolved by year three, as predicted, was an added disappointment of ABSORB II. Some of the poor outcomes could well be attributable to remnants of the stent persisting in the vessel. That being the case, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) may need to continue for trial participants an additional six months and possibly a year or more. Stopping therapy too soon may put patients at risk for a cardiac event, but continuing it creates a prolonged delay for those needing or wanting electives procedures such as a colonoscopy and an added hazard if any sort of surgery is required prior to DAPT termination.

That being said, the Absorb stent still has promise. Remember, drug-eluting stents didn’t reach their full potential until the second or third iteration of the technology—after we figured out the importance of deploying at high pressure with good image acquisition, and understanding the upstream and downstream impacts of treatment on the occluded vessel. It would be too soon to abandon the quest for a disappearing stent, but we do need to proceed with caution.

The good news is that the first U.S. trial now underway is limited to 250 investigative sites familiar with the unique details involved in proper sizing and deployment of Absorb stents. The new approach being tested involves better vessel image acquisition with intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography (80 percent of catheterization labs already have one or the other) before selecting the stent size for implantation in order to ensure a precise match. So the stents can potentially be successfully deployed, even at high pressures, without fear of potentially breaking the horizontal struts—especially since physicians will be strictly following indications for use in patients with coronary artery lesions having a reference vessel diameter of between 2.5 mm and 3.7 mm, and optimize vessel preparation by either performing prior angioplasty or atherectomy, prior to stent deployment. I expect the results will be far better than what came out of ABSORB II as we use this “vessel preparation” approach in the right subset of patients.

In the interim, drug-eluting stents that reside permanently in the vessel remain the gold standard for percutaneous coronary revascularization, with one year of DAPT to prevent clot formation, until the drug-eluting matrix and stent have been re-endothelialized.

Share Email Medical Devices, Patient Experience