HealthTrust Members Apply Lessons From Disasters & Emergencies to Future Planning

When a shooter opened fire on an outdoor concert in Las Vegas in October 2017, the number of critically wounded patients threatened to overwhelm emergency responders and hospitals. In the hours that followed, Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center in Las Vegas, Nevada, saw more than 240 patients, 124 of whom had gunshot wounds—the largest mass casualty shooting event in modern U.S. history, says Todd Sklamberg, CEO at Sunrise Hospital.

The Joint Commission guidelines require healthcare organizations to have plans in place for responding to natural and human-caused or terrorist-related disasters and emergencies. Those guidelines require regular training to prepare staff and resources throughout a facility for optimal performance in the case of such an event.

“HCA Healthcare has had decades of experience in emergency operations management dating back to the days after 9/11,” says Michael Wargo, RN, BSN, MBA, PHRN, vice president of enterprise preparedness and emergency operations for HCA Healthcare. “HCA Healthcare has incident management teams at every facility that undergo intensive training that includes working through crisis scenarios. When a crisis happens, our approach is to organize locally, coordinate at the division level and strategize at the corporate level. This gives us economies of scale and takes the burden away from individual facilities to do all the work themselves.”

When events like the Las Vegas shooting or natural disasters occur, facilities—and their communities—see firsthand how those emergency preparations play out, and what should be adjusted next time.

“Unfortunately, the question is not whether this will happen again, but where and when,” Sklamberg says. “As healthcare leaders, we have a responsibility to prepare our facilities to handle such events to the best of our ability.”

Expect the Unexpected

Though planning and drills can help facilities respond to crises, it’s impossible to prepare for every eventuality. As the Las Vegas crisis unfolded, Sunrise staff were required to respond to one unforeseen event after another. “The events of Oct. 1 were so unique, there’s no way we could have prepared specifically for them,” Sklamberg explains. “But our drills gave us the foundation we needed to scale up.”

For example, 92 of the injured patients at Sunrise had no identification at all, so staff had to work toward identifying them in order to reunite them with their family members. One team of social workers and other staffers began interviewing family members as they came in, asking for descriptions of their loved ones. Another team went through the hospital, writing descriptions of the patients who did not have any identification. Yet another group sat in a room and matched the family members’ descriptions with the staffers’ descriptions. “It took about six hours to identify everyone,” Sklamberg adds. “Body art and piercings helped a lot.”

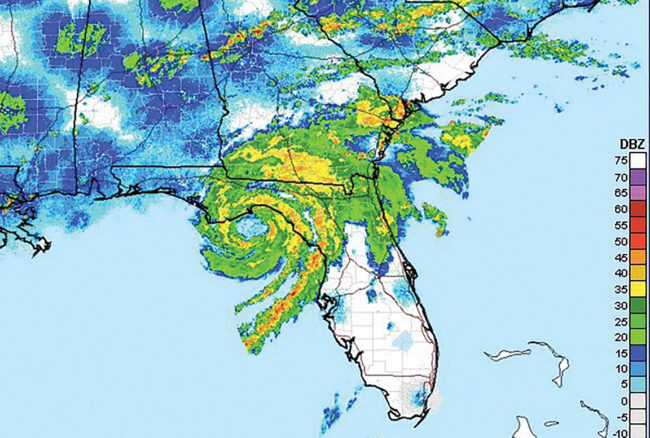

Preparation is a necessity, “but a disaster or emergency is never going to happen the way you expected,” says Tom Lawhorne, CFO at Regional Medical Center Bayonet Point in Hudson, Florida. On Aug. 31, 2016, as Hurricane Hermine was churning in the Gulf, the coastal hospital was prepared for an influx of patients the following night, when the hurricane was expected to make landfall 100 miles north. About 6:15 p.m., when most staffers had left to prepare their homes for the incoming storm, power went out in the hospital. Lights flickered as the emergency generators tried to kick in, but within a matter of seconds, the facility was completely dark, Lawhorne explains.

A lightning strike caused an electrical fire on the roof, taking out all access to power. Bayonet Point’s emergency drills had always been conducted in the daytime with the CEO, COO or assistant COO (ACOO) taking the lead. When the fire happened, top leaders were either out of town or on medical leave, the roles of ACOO and emergency preparedness coordinator were vacant, and the plant operations director was brand new in the role. Lawhorne was the only C-level staffer available, and he happened to be working late that night.

“We had no power or generators, and none of the people who had run the drills were here,” says Lawhorne, who had only a flashlight and a cellphone.

The computer and phone systems were also down, so Lawhorne had no way of communicating with staff throughout the facility. When the fire chief needed to know how many people were in the building so they could properly evacuate everyone, “We got the word out by word of mouth, cellphones and social media,” Lawhorne says.

Even when a disaster is expected, there are likely to be surprises. Gonzales Healthcare Systems in Gonzales, Texas, held meetings twice a day for several days before Hurricane Harvey made landfall in late August 2017. They were prepared with essential supplies and enough staff to support current patients and up to 250 extra patients and visitors for a maximum of five days. But then they were faced with the unexpected: “When the storm was at its worst, we lost power and had to control water going under some of the doors,” says Steven Ackermann, director of materials management. “I had people coming up to me asking, ‘Where can I help?’ We came together as a team and got the job done.”

Managing Staffing Challenges in Times of Disaster

When disaster hits, most healthcare facilities need extra staffers to help handle overflow traffic or maintain increased patient loads over several days. For instance, when Hurricane Harvey hit, Gonzales Healthcare Systems in Gonzales, Texas, was adequately staffed, but “it would have been easier for everyone if we would have had more staff on hand from the beginning,” says Steven Ackermann, director of materials management. “When people left work on that Friday, they couldn’t make it back to help until Sunday night due to the winds and flooding.”

Unfortunately, the nature of hurricanes, mass shootings and other disasters means that facilities will be caught off guard to some degree, says Brendan Courtney, president and CEO of HealthTrust Workforce Solutions. “However, the extent to which your staffing operations are impacted often comes down to how well you’ve prepared in advance,” he says. “The best approach is to have a strategic plan to address how your business will react to the immediate and evolving needs that will inevitably arise.”

According to Courtney, achieving staffing continuity requires a multidimensional approach that gets the right people to the right place at the right time. In moments of crisis, medical personnel are often willing to answer the call to serve in uncertain circumstances. For instance, in 2017, HealthTrust was in contact with more than 1,000 nurses who volunteered to serve communities affected by Hurricanes Harvey and Irma.

To support healthcare organizations in times of crisis, HealthTrust Workforce Solutions created the Disaster Response Team, a special group made up of a wide variety of clinical professionals with broad geographical representation. “Disaster response team members must be highly adaptable and resourceful, willing to pick up and deploy when and where they are needed at a moment’s notice,” Courtney explains. “We assess clinician interest and availability on a regular basis, usually in advance of forecasted times of need such as hurricane season. It is imperative that these clinicians be fully credentialed at all times. Even in the worst crisis conditions, quality can never be compromised.”

In addition to identifying seasoned professionals who are ready to answer the call to serve, facilities also typically encounter logistics challenges. HealthTrust’s corporate operations in Sunrise, Florida, coordinates crisis relief staffing efforts with regional and localized command centers established near the disaster location to provide on-the-ground support.

“Constant and consistent communication among these corporate and regional command centers, as well as the disaster response team itself, are critical to the overall success of the workforce disaster response,” Courtney says. Sometimes it takes flexibility and resourcefulness to get qualified professionals to places dealing with hazardous conditions. This past fall, HealthTrust Workforce Solutions utilized duck boats and helicopters to ensure nurses were able to access a flooded facility during Hurricane Harvey.

“While the first step in responding to a crisis situation must always be to execute your predetermined continuity plan, you can never underestimate the critical impact that quick, out-of-the-box thinking can have in times of desperate need,” Courtney adds.

Preparation Pays Off

Even though the Gonzales team may not have prepared for severe flooding, their focused training mobilized the facility’s staff to be ready for almost anything. Although any disaster or emergency will be fraught with unknowns, careful preparations make a positive impact on how facilities are able to cope.

Bayonet Point staffers had never trained for an electrical fire that would eliminate all power, but they had been trained to think on their feet in an emergency. A so-called “old school” house supervisor who had never abandoned her hard-copy patient census was able to refer to her list to ensure that every patient was evacuated and each family was contacted, Lawhorne says. Because the phones weren’t working and there was no way to make large-scale announcements, leaders on each floor took over their units, manually ventilating patients with bag valve devices and carrying patients down the stairs in the absence of working elevators, he explains.

Staffers felt empowered to make the right decisions for their own areas in the event of a crisis, which allowed the hospital to evacuate 225 patients in eight hours with no negative patient outcomes or injuries to emergency staff.

Emergency preparedness also facilitates a focus on collaborative teamwork. As word got out about the fire at Bayonet Point, off-duty staff members just started showing up to help evacuate patients, find places for them to go, and do whatever other tasks were needed. Physicians and staff members accompanied patients being evacuated to nearby hospitals to avoid an interruption in care.

After the shooting in Las Vegas, “Our colleagues rose to the occasion,” Sklamberg says. “The teamwork we saw that day was remarkable. We had phlebotomists working in the ER, a pediatric surgeon serving as a scrub nurse, and another pediatric surgeon operating on adults. Multiple people just put aside their normal roles and responsibilities to do what was needed.”

In the aftermath of the shooting, Sunrise staffers made an early triage decision that helped organize and manage care throughout the night. They stationed an ER physician at the door to assess injuries and send patients where they needed to go: Walking wounded went to a waiting room, while those in critical condition were moved to trauma rooms where they were stabilized or resuscitated. At that point, patients were sent to a second level of triage based on their wounds: Those with gunshot wounds to the head were sent to an area where neurosurgeons were waiting; those with chest wounds went to the thoracic ICU where cardiac surgeons were on standby; and those with orthopedic injuries were sent to a separate area for care.

“As specialists came in, they were dispatched to the area of their expertise,” Sklamberg says. “It made for an efficient and effective process and contributed to our success.”

Systematic preparations also help facilities build closer relationships with local emergency response agencies, which is crucial in a time of crisis. For example, before Hurricane Harvey hit, Matagorda Regional Medical Center in Bay City, Texas, had built a dome with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which allowed the hospital to house first responders and essential personnel during the hurricane and its aftermath.

“Luckily, many of our personnel were also a part of the Matagorda County Emergency Operations Center (EOC),” says Travis Ursery, materials management supervisor. “The EOC provided real-time expertise and support before, during and after the event, and the first responders ensured that we could reopen as quickly and as safely as possible. Our advanced planning also allowed us to stand up a makeshift urgent care center long before the hospital and the medical group were operational. We were able to provide basic medical services to our community and surrounding areas, which took some of the pressure off of first responders and medical personnel located in areas that were harder hit.”

Planning for the Future

After experiencing a large-scale disaster, it’s wise to reexamine emergency preparedness and make necessary adjustments based on what you learned. For instance, after losing power and phone systems, Bayonet Point’s Lawhorne says his facility now has a cellphone text group so that leaders can immediately text staffers in the event of a crisis. His facility has also shared its emergency phone tree with nearby hospitals so that another hospital could activate it if necessary. In addition, Bayonet Point has placed compact flashlights throughout the hospital, as well as headlamps—a tip staff learned from the crisis.

“If you’re trying to a carry a patient, you can’t hold a flashlight,” Lawhorne says.

In Las Vegas, cell towers went down because of the overwhelming number of phone calls following the shooting. As a result, Sunrise is moving to an automated phone system for use in case of emergencies. Sunrise is also working closely with emergency responders to enhance the process of tagging patients and provide more advanced equipment in emergency preparedness kits.

Even though no hospital can prepare for a specific emergency, those who have been forced to use their emergency plans say the practice drills are critical.

“Go over your disaster plans with all of the staff and make sure they clearly know their roles,” Ackermann says. “Take all drills seriously, and make sure the staff knows emergency preparedness is a vital part of their jobs.”

Above all, be flexible and listen to feedback, Ackermann adds. “Your staff may see something in your plan that needs to be tweaked or changed all together.”

Share Email Disaster & Emergency Preparedness, Patient Experience, Q3 2018, Surgery